I entered law school after college, and a friend from law school invited me to join him in his native Hawaii to work on a consulting project to assist the Territorial Government of Hawaii make the transition to statehood. I began to understand public personnel administration based on studies I participated in for the personnel systems of the City and County of Honolulu and the Territorial Government, as A Job: Defining the Core Element of Work and Organizations well as studies for the Trust Territories of the Pacific and American Samoa. It was interesting work. It was in that role that I learned about two things that shaped my development and informed my career to come: The first was what a “job” is. I had never really thought much about this before, but I learned that the

standard definition was that a job is a bundle of duties and responsibilities and is the building block of every work organization. I learned that describing a job and its relationship to other jobs was something of a science and was essential to the development of effective organizations and to departmental structures in larger organizations. It was also a means of arriving at a sensible compensation system. In my work with him, it was a critical part of determining how organizations in the then Territory of Hawaii might be restructured to be more cost-effective and rational in terms of services that various governmental agencies should be designed to offer.

In the job evaluation process, we not only considered duties and responsibilities, but more obscure characteristics about motivation, training and developing staff, and other matters that clearly were important to getting work done. In those days, organization theory focused more on issues related to structure than “human” relations matters. Neither my friend nor I returned to law school. The world of human resources proved too interesting.

One of the principal books of organizational theory for that era was one by Luther Gulick and Lyndall Urwick. From this book, I learned that the key functions an organization and its management were responsible for were planning, organizing, directing, staffing, coordinating, reporting, and budgeting. To this list, the team I had joined believed that motivating staff and teams was a crucial part of any management job. That early exposure was a great prelude to my later consulting in organizations for it was where I first began to understand the chain of command, the need for clarity about organization structure, the importance of organizational goals and imbuing employees with an understanding of goals, and so on.

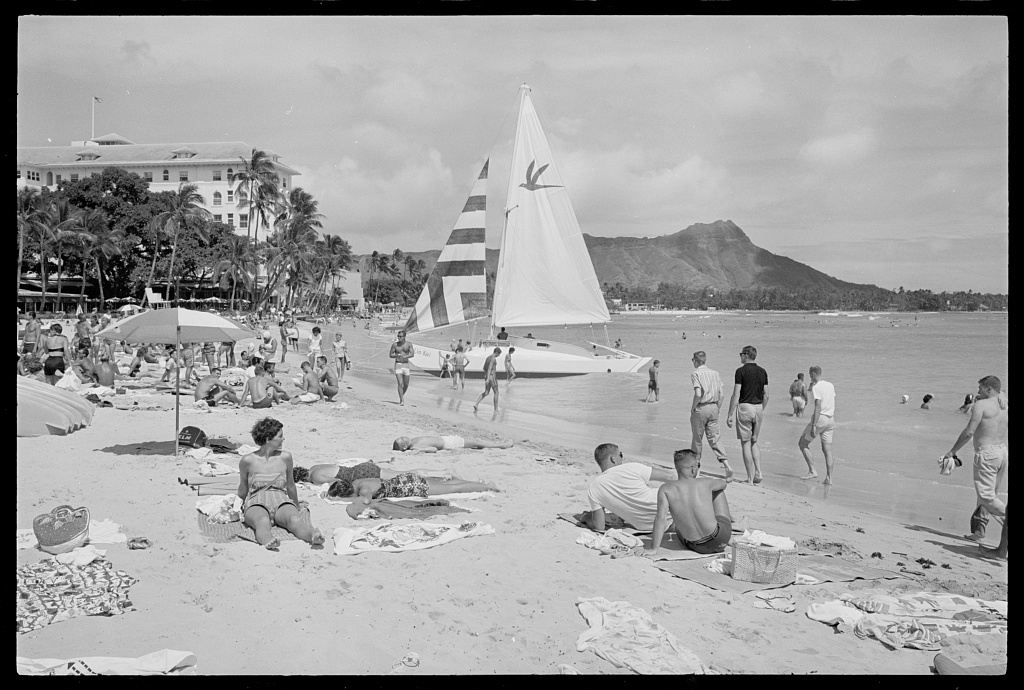

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)